The Bayeux Tapestry is one of those iconic bits of world history on a par with the pyramids, Big Ben and the tree in Barnes where Marc Bolan crashed his Mini.

One of the main attractions in Normandy northwest France, the tapestry is housed, unsuprisingly, in the medieval town of Bayueax, 10 kilometres from the coast. Now 1000 years old, depicting the Norman invasion of England in 1066, there is disagreement over why it was made, by whom, where and what some of its content actually means. What is agreed is that it is an embroidery not a tapestry and is 70 metres long. Our tour guide went with the opinion that it was made in England and avoided saying it was a rather splendid piece of Norman propaganda in defence of the invasion.

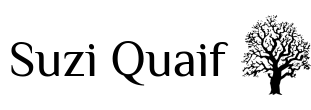

If it was made in England, and there is a lot of reasons why we should think it was, then it is most likely the very last example of Anglo Saxon art ever made. It is now generally accepted that it was commissioned by William’s half-brother Bishop Odo, which is borne out by his appearance in the work along with three of his followers. As we can never be able to get inside the head of a medieval man (or woman) it is accepted that there are parts of it whose meaning we can only ever guess at. Not surprisingly it has been restored a few times and is thought to have lost a metre and half at the end.

Originally it was kept in the 11th Century Bayeux Cathedral and rolled out for public viewing for a week every year on the Feast of St John the Baptist. Now it’s kept in the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux, a grand building that was once the Bishops Palace.

It took us a while to find the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux , the French having the same attitude to signs as the Irish; take you so far then leave you wondering. Eventually we did find it, through an impressive doorway to an expansive courtyard. In the entrance hall of the museum a life size representation of William the Conqueror on his charger oversees the peak season queues winding their way through the airport check in system. As it was off season at the time of our visit in early May and the entrance hall all but deserted, we paid our due and went in.

The tapestry, kept on one side of a long dimly lit corridor, is stretched out behind glass to be viewed while listening to the dulcet baritone’s of the scene by scene commentary on what looks like a retro cell phone.

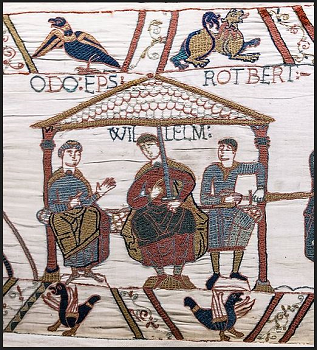

What we see so often in the media are individual scenes, some more famous than others, but this does detract from what a wonder it actually is. It is an extremely effective storyboard created to record an important piece of history in a time when few could read and heritage was passed on word of mouth through poems, songs and storytellers. There is explanatory text (tituli) in Latin that, we were reliably informed, drifts into Anglo-Saxon, but the story moves through sequential action pictures and significant gestures. In 1800 scene numbers were added in ink and have been used by everyone since to tell one scene from another, including our dulcet toned commentator.

The only real way to appreciate the skill of it is to view it from end to end though all of its 57 scenes. The central story runs down the centre bordered above and below by mythical creatures, side scenes to the main panel and scenes from life of common people. It has drama, death, hand to hand combat, gore, deception, daring do, sexual indiscretion, and the daily doings of everyday folk. All the elements of a decent Coronation Street storyline.

It is very  male dominated, there are few females depicted and even fewer with any clothes on. The husband loved it and I am ashamed to admit that I regressed to a 3rd year on a school trip when we happened across the rude bits.

male dominated, there are few females depicted and even fewer with any clothes on. The husband loved it and I am ashamed to admit that I regressed to a 3rd year on a school trip when we happened across the rude bits.

The rude bits, censored by the prudish Victorians and sensible primary school teachers, appear as ‘sub plots’ in the borders and range from just nudity to the explicitly erotic. None give any clue as to what they are meant to depict, but would seem to depict sexual indiscretion or rape. It could be that they simply depict the gossip of the time, or if it’s viewed as Norman propaganda, the actions of the English troops on the move.

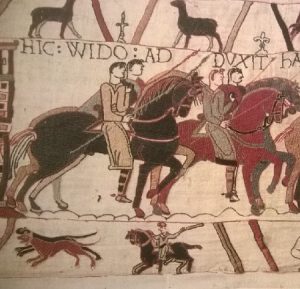

Perhaps the most argued about bit of nudity is added to the scene where William and Harold spend time together in William’s palace at Rouen.

In an interview given to the History Today podcast, Laynesmith (Joanna Laynesmith, a medieval historian from the University of Reading) explains that the illustration seems to be the subject of a conversation between Harold and William where they are “talking about something in the past.” The next scene shows a woman named Ælfgyva with a priest, along with the caption VBI VNVS CLERICVS ET ÆLFGYVA (where a certain cleric and Ælfgyva) Laynesmith adds that the scene also shows “a naked man who exactly mirrors the pose of the priest who stands next to Ælfgyva. The priest is reaching out and he has hands on her face – whether he is hitting her, carressing her, you couldn’t say. You have this figure underneath who is very well endowed, and that has given rise to a lot of suggestions that there was some sort of sexual scandal involved here.”

Source : Medievalists.net November 13, 2012

The scandal is believed to be that the first ‘wife’ of King Cnut (she is sometimes referred to as a concubine or handfast wife) Aelgifu of Northampton, who it is said, had an affair with a priest and convinced Cnut that the resulting baby (Svein Knuttson) was his son. Her other son by Cnut, Harold Harefoot, so it’s said, was actually the adopted son of a cobbler. It’s also thought that the scandals may have been rumours begun by Emma of Normandy, Cnut’s other wife. What did I tell you! Shades of Coronation Street

What can’t be denied is that neither William nor Harold had a strong claim to the throne of England. They both could cite tenuous connections to Cnut and Emma of Normandy, parents of Edward the Confessor. Edward the Confessor himself was only stepson to Cnut, his parents being Emma and Elthered the Unready, Emma’s first marriage. Harold was the son of an earl who was brother in law to Cnut’s sister. William on the other hand was the illegitimate son of Robert Duke of Normandy the nephew of Emma, earning him the nickname of William the Bastard.

The intention of the rude bit in Rouen may be to imply that Harold’s line was sullied by a woman with dubious morals. A couple of days into researching Medieval history I came to the conclusion that power corrupted and even a hint of succession to absolute power invoked moral abandonment and seriously anti-social behaviour

The intention of the rude bit in Rouen may be to imply that Harold’s line was sullied by a woman with dubious morals. A couple of days into researching Medieval history I came to the conclusion that power corrupted and even a hint of succession to absolute power invoked moral abandonment and seriously anti-social behaviour

Whatever the intended meaning of the sub plots, footnotes and interesting asides of the tapestry it has, quite rightly, become a legend in its own right and I’m sure will be the subject of fascination for another 1000 years.

Whilst researching I also happened across an article reporting that in 2014 the missing metre and a half had been recreated in Aldernay in the Channel Islands. At the end of 2016 it was doing the rounds in Jersey and Guernsey. Click on the link to read more.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-28018096

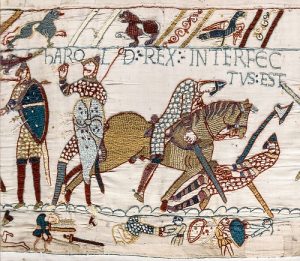

I can’t really leave the Bayeux Tapestry without mentioning the arrow and Harold’s famous death scene.

According to a Norman account, Song of the Battle of Hastings, by Guy Bishop of Amiens, Harold was killed by four knights, including William, and his body dismembered. The death scene does show Harold falling backwards in front of a horse whose rider is hacking at his thigh with a sword. The arrow itself is part of the later restoration as is the wrong colour to be original. The original pin holes and a very early replica would indicate the arrow was originally something else. To add to this, common medieval iconography of a perjurer was to die with a weapon through the eye and Harold certainly did swear an oath of fealty to William then break it. I don’t suppose we will ever know the truth, but the arrow in the eye has become the stuff of legend known and loved by everyone from school age upwards.

Ever since I walked out of the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux I’ve had the fond feeling that the tapestry has far more of the English in it than it might seem. It was designed by a person of implacable intention I’m sure, but in my version of history it was given to a bunch of recently subjugated Anglo-Saxon women to embroider who maybe just wanted to leave their mark.

‘’Ere Ethel. Has thou forgotten summat lass? According to yon plan that there chap bent over his broad axe has a tunic on’

‘Nay Nora. You leave him be, he’s quite happy as he is’

All Rights Reserved